You Could Try One

How We Learn

Swim

Bike

Run

Open Water Swims

Warmup/Cooldown

Wetsuits

Tech Wear & Tri Suits

Rules

Stretching

Strength Training

Nutrition Basics

Losing Weight

Nutrition For Athletes

Race Nutrition

Race Lengths

Training, Tapering

Cramps

Creaky Knees

Gadgets

Running Shoes

Gear Checklist

Race Day

Picks & Pans

Warning Label

Marathon (the song)

Also Try Feldenkrais

Training & Tapering

Getting stronger is all about stress and rest. Except that sounds like a bad rhyme. So let's call it Stress and Recovery. Exercise lays the groundwork for getting stronger, but when you finish exercising you may be momentarily weaker. The getting stronger happens in the hours and days afterwards. The body notices what you've been doing and sets about repairing and improving. However, if you don't ever stop long enough to allow the body time to fix things up, you won't get stronger, you'll just get weaker.

I can remember the running coach from the University of Chicago came and talked to the Evanston Running Club many, many years ago. He'd had a lot of success with his runners and someone asked him what his secret was. He shrugged modestly and said, "Well, you know, these guys I work with don't need motivation from me. They're incredibly motivated. The main problem is that they tend to train too hard. So one of them will come to me and tell me their times are slipping and they're feeling sluggish. And I give them my stock answer, Take the day off. I've built a coaching career out of saying, Take the day off." This macho devotion to hard training is a disease among triathletes. We are a culture of tough people who push ourselves. Yes, you need to consistently do the work. But you must also allow yourself to recover. Constantly hammering your system will not make you stronger.

What a triathlon coach does is to design a program that very gradually increases the stresses on your body and leaves time for recovery. If someone is just beginning in triathlon, a perfectly fine schedule would be:

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| Run | Bike | Swim | Rest | Run | Bike | Swim |

You'll notice that you don't have a lot of rest days. But the muscles that are used when running are only stressed every third or fourth day. Same for biking and swimming. There's plenty of time for recovery. The day of rest is more just to ensure that you don't overtrain. Why are we so worried about overtraining? Because it really can do you in. There's something called overtraining syndrome that can just sap your energy and leave you needing months to recover and start feeling normal again. Overtraining also increases your chance of injury.

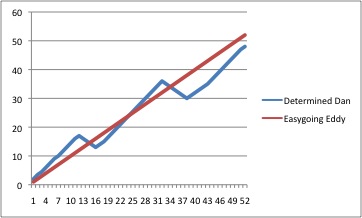

To make a point I want to take a look at a year in the life of Determined Dan and Easy-going Eddy. Determined Dan simply works harder and pushes himself harder. It's not that Easy-going Eddy doesn't work hard. But he listens to his body, allows for adequate recovery, and just isn't that driven. So here's their progress over the course of a year.

Those bumps in the graph are where Dan had to take a month off to recover from an injury. And the reality is that some people with Dan's attitude don't get injured and manage to end up on the podium. But many more get hurt along the way and don't make steady progress. There are even some who decide they're just not tough enough for the sport and quit.

Sleep

I'm going to say it again. You don't get stronger from stressing yourself. You get stronger because you stressed yourself (past tense) and now you're body is being given the down time it needs to make your stronger. The best time for that is when you're sleeping. Get plenty of sleep, at least eight hours a day. Take a nap in the middle of the day if you need to and can manage it. I would advise not getting up to an alarm clock. Sleep is more important than the exercise session you might miss. Just sleep in and go to bed earlier that night until you can get up early and refreshed without being dragged out of bed by the alarm.

Two Workouts A Day

When people move beyond the sprint distance, most find themselves resorting to two workouts a day. Take what you know about rest and recovery and study the advanced workout chart below.

| Sun | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | Swim | Long Bike | Bike | Bike | Long Run | Bike | Run |

| PM | Run | Swim | Run | Swim | Rest | Swim | Bike |

You'll notice that when I have to do a run two days in a row, as with Saturday and Sunday, I try and give myself a day and a half of rest by doing the run in the morning of the first day and the afternoon of the second day. I worry about that less with the bike. So let's criticize the plan. If it's the summer those two runs in the evening could be tough. Usually in warm weather it's better to run early before the heat sets in and while the air is relatively unpolluted. Trouble is, if on Sunday I switch the Run to the morning and the Swim to the evening, I'll have only 24 hours to recover from the Saturday Run and only 24 hours to recover from the Sunday Swim. And can I even get into the lap pool on a Sunday afternoon? Sometimes you're forced to make compromises just because you have to mesh with pool schedules, family time, etc. Developing a schedule is complicated. A lot of triathletes will do extensive workouts over the weekend just because that's when they've got the time. I feel for them, but I don't think doing your long bike and long run back to back is a great idea. Give yourself a couple of days in between. Sounds like I expect you to get up at 5 a.m. to workout. There are worse ideas, especially in the summer. You'll need an amenable spouse, but if the two of you are willing to be head on pillow by 9 p.m., why not? One point about the long run. That's the most stressful session you'll do. It's hard on the body. Doing say 18 miles once a week is too much. You need perhaps 10 to 14 days to recover adequately. Unfortunately, our weeks are 7 day, so people fall into a pattern of doing a long run once a week. Try and avoid that. If you want to keep a consistent schedule (and there's a lot to be said for doing so), make every other "long run" something easier, say a 10 miler.

Brick Workouts

You'll notice in my schedule you don't see any workouts with a hard bike followed immediately by a long run. (When people talk about a "brick workout," this is typically what they mean.) This is the disease of triathlon. We always seem to be punishing ourselves. Yes you'll have to do this in a race. But you don't have to do this in training. On the other hand, there is a reason for running right after biking. In a race this is a tough moment. You've racked your bike and you step out for your run and your legs are asleep (or they feel like telephone poles, or however you want to describe it). It's a tough transition as the blood gets redirected. So a most excellent idea is to do a ten minute run immediately after you've been on a long ride. It teaches your body to make the transition. But within ten minutes you'll be running normally. Done on a regular basis it allows the body to figure out how to make the switch. But a long run right then isn't necessary. I realize you'll see such brick's recommended elsewhere. I don't see the point. The term "brick" is actually a little more generic than that. It can refer to any combination of workouts. So you get out of the pool and it's pouring rain outside and the gym has a nice indoor track so you think what the heck and you put on your running shoes and get it done. But I'm not doing it to wreck myself.

Logging Your Workouts

It's essential to log your workout on a calendar or in a log book of some sort. I started logging my workouts as a runner, and I’d note how many miles I’d run. I was running better than 10 minutes per mile, so whenever I didn’t know the distance (this was 40 years ago before GPS) I’d just divide the time by 10 and use that result as my distance. In other words, a 2 hour run was worth 12 miles. At the end of the week I'd add up the miles and know what I'd done that week. I could then compare that with the sort of mileage recommended for the distance I was planning on racing. When I started doing triathlons I took the same approach I'd used when running by converting time into "miles" for the bike: 10 minutes equaled 1 point. That way I could connect and compare the miles of running with the time on the bike. Swimming was difficult, because I wasn’t swimming continuously. Time in the pool wasn’t a reliable indicator since time spent hanging on to the side of the pool wasn’t exactly exercise. Yards were, though. So I adopted a conversion of 1000 yards being worth 3 points. (This assumed I could do a 1000 yards in 30 minutes. The trouble is, that changes the more you train. The time required to do the 1000 yards is creeping lower, and yet I'm still giving myself 3 points per 1000. It was a good value in the beginning, and now for the sake of consistency I've kept that value. You might eventually decide to make it 2 points per 1000.) What this gives me is three different numbers for the three sports that allows me to see which sport is getting more effort than another and allows me to add the values together for a weekly total that tells me how much stress I put my body through that week. Which then allows me to compare one week with another, one season with another, and one year with the next. Part of the reason is motivational. I feel good about a calendar full of numbers. They represent the effort I've put in. But it also allows me to see trends. If I'm feeling sluggish, maybe I've been doing too much. I ponder the log. Felt great today. I ponder the log. You learn from it what works for you and what doesn't. I want you to see an example of how all this would work, so below is a possible schedule (a rather heavy one for someone working up to an Ironman). For each box there are three lines: activity, how much done and points. The bottom row is the total points for each day.

| Sun | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | Swim 3000yds 9 | Long Bike 3 hours 18 | Run 6 Miles 6 | Bike 1 hour 6 | Long Run 18 miles 18 | Bike 1 hour 6 | Run 6 miles 6 |

| PM | Run 6 miles 6 | Swim 3000 yds 9 | Rest | Swim 3000 yds 9 | Rest | Swim 3000 yds 9 | Bike 1 hour 6 |

| TOT | 15 | 27 | 6 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 12 |

So my total for the week adds up to 108 points. (I haven't included strength workouts or stretching. You might choose to.) If you convert the points to hours it comes out to 18 hours for the week. The individual totals are run: 36, bike: 36, swim: 36. In other words, a very even distribution. You'll notice Monday is a tough day, but it's made up of the disciplines easiest on the body. When I do a long run I'm usually wasted the rest of the day so Thursday afternoon is a time of rest.

So let's imagine a triathlete doing consecutive weekly totals of 98, 104, 108, 116, 124, 130. Anything coming to mind? What occurs to me is, gosh this guy's going to be a total disaster soon. You just can't keep loading on like this and not expect things to break. Over time, you should gradually increase the load you're carrying. But again, you don't want to risk overtraining syndrome. So smart coaches build in recovery weeks. They'll plan two hard weeks followed by an easier week. Or three hard weeks followed by an easier week. Whether they're using a three or four week cycle is based on the person they're coaching. Some people handle stress better than others. On a three week cycle the pattern might look like this: 98, 104, 84, 102, 108, 90. I'm in my sixties now, so I usually go with a three week cycle just to be safe.

Where To Focus

I think there's a tendency to focus on the sport you're best at. And obviously, that's a mistake. You need to focus where you're weakest. In the beginning, for most people, that will be the swim. You can't fake the swim. In a sprint race where you're just trying to get to the finish line, most can get through a 12 mile bike ride with little preparation. Just get on the old Schwin and peddle for an hour. Coast when you need to. On the run you can even walk when needed. Just keep the legs moving.

Things change when you get past the sprint. In time you get so you can swim long distances. It takes forever to get good at it, but you get there. It's the shortest part of the race and increasing your speed on the swim eventually gets harder. Where you could fake the bike in a sprint, at longer distances you'll really feel it if you're weak on the bike. It's the longest part of the race and if you're just hanging on for dear life (been there, done that), you're not going to have much left when you start running. So what was once fake-able becomes the most essential aspect to finishing well. If you're trying to win the race, it all seems to come down to your endurance on the bike and your speed on the run. And since we're talking about hours on the bike, you better build up your strength there.

Racing

You don't really need to love racing to be a triathlete. I have mixed feelings about racing. Part of me really looks forward to racing. And having a race on the horizon does wonders for your focus and sense of purpose. All the training you're doing is getting you ready for something. But racing interferes with training, and I rather like the consistency of training. I'm also aware that I'll have to face down some fears and put up with some pain when I race. The reality is, racing is not all euphoria. But it adds shape and meaning to your efforts. In truth, one race a season is enough to give you a goal. You don't need to race every weekend. If you're racing every weekend along with a modest taper and a couple of days recovery, well there's no time left for training. And in the long run a consistent training plan is what it's all about. So find a happy balance. I like having some small event maybe once a month. There are events in the individual sports that are a nice change of pace. So if there's no sprint tri that fits my schedule, I'll sign up for a 5K or an open-water swim or a bike ride. Since you do want a week of easier training at least once a month, just design your schedule so such races fall in your recovery week, and you're all set. Be forewarned that triathlon race fees can add up. Those shirts are expensive (no, not for the race organizers, they're expensive for you).

Periodization

Periodization is a fancy word for "training has different seasons." Typically a triathlete finishes her last big race in the fall. The day after she'll lie in bed feeling rather sore and not anxious to be on her feet that much. She will never-the-less look at the schedule of next year's races and start to plan. Here's the most important race. Here are some other races that would be fun to do and might actually help her prepare for the big one. She wants the spacing right. Races two weeks in a row might not be a good idea. She then fills in a training period for the winter where she's trying to build up her aerobic base. That feeds into a period of increasing speed work to get herself set for racing fast. Then she'll taper for several weeks in preparation for the "Big One." Finally she assaults whatever mountain she's set for herself. And the first thing on her list as she begins the year of training? PARTY! Or at least, take it easy for a while. Most serious athletes will mix things up a little for a few weeks at the end of one season and the beginning of the next. Get some cross training in with some sports they normally don't have time for. Or even take a week off and be lazy. It's a time to recharge the batteries. So a year might look like this:

Month 1: Recovery

Months 2 - 6: Build aerobic base

Months 7 - 11: Increase speed work and do some racing

Month 12: Taper before big race

Day 365: Race the big one

And then she'll start it all over again.

Training To Race Year Round

This periodization business works quite well when you live in world of seasons. I'm north of Chicago. We don't do a lot of triathlons in the winter. (That was a joke. Lakes get frozen in the winter. No triathlons unless you want to do it in a gym on a stationary bike.) But if you live in California and you're not trying to win the national championship, you may be wondering, what's the point? And you're right. You can design a program that keeps you ready to race year round. Keep some speed-work in each week (I do this anyway). Keep yourself fresh by not overdoing. Race all year round. Just have fun with it.

Planning A Year

So I'll share the planning that went into my own schedule for this year (2011). Maybe listening in will help you in your thinking. You start with long-term goals. I'm thinking I'd like to attempt the Ironman in September of 2012. So that leads me to think that doing the individual components of the race in 2011 would be a good idea. I'd like to be able to function at that level 12 months out and then just give myself a year of maintaining that level in preparation. (Anyhow, the race I'm shooting for fills up within hours one year in advance. So doing it this year isn't an option.) So I begin by putting several main events on the calendar. I'll do a marathon in October of 2011. Earlier that year I'll do a half Ironman. In preparation for that I'll do a long swim race. And about a month before the marathon I'll do century bike ride (100 miles). I then figure out a few more events that I want to do, some shorter triathlons or runs. Once those events are on the calendar, I start figuring out a training regimen.

Winters a good time to get my hours up in the pool. So that will be my focus then. Winters are also a wonderful time to put in the hours on the Computrainer as I watch some movies. If I'm going to do a marathon, I know I'll want to gradually increase my long run mileage over the course of the year. I'll want between 10 and 14 days between long runs so my body has time to recover and adapt. So those go into the schedule first. The timing of those are adjusted so they don't interfere with the races I've planned. Up above I talked about giving yourself an easy week at least once a month. I try and set up a pattern so my easy week becomes my taper week before a race. I also know I'll twice be away at a dance camp for almost a week, I know my tri training's going to fall apart for those days. But instead of feeling like the world will end if I let up on my training, I tell myself those will be much needed recovery weeks from the stress of training. So the first get-away becomes part of an easy week. The second camp comes a week after the half Ironman race, so that vacation really will be part of my recovery time. Once I'm home from that, I'll cut back on the swimming and put some of that energy into upping my running mileage in preparation for the marathon. If I find that one of the less-important races I had planned on just doesn't fit into the schedule well, I'll drop it. Don't let your big goals get screwed up because you're impetuously going out and racing every weekend. (Though a short 5K isn't enough to screw up your training and is actually good for you. You benefit from short intense efforts.)

Tapering

You cannot cram for a race. You cannot put in some serious training time in the final weeks in order to make up for all you should have done all year. Training doesn't yield quick results. There is some serious repair that happens the first day after you train, but some of the changes take weeks to complete. During training you will live with a certain level of aching fatigue. You'll get so used to it you'll hardly notice. It becomes the air you breathe. You'll become Superman, but a tired Superman. Before the big race you want all that system-wide, low-level fatigue to fade away. That means taking it easy. A long run pays dividends over the next few weeks. And until you've fully recovered from it, you may actually be damaged in subtle ways. So when a big race is coming up you need to back off. On the morning of the big race you need to be fully recovered from the travails of training. Otherwise you might add the final straw to an injury in the making and come up lame before getting to the finish line. The best way to avoid disappointment is by diminishing the volume of training you're doing. The problem here is that, if you stop exercising entirely you're body will quickly notice that you don't need to be Superman any more and will start dismantling things. You'll lose conditioning. A couple of days off is great for you. Three weeks off would be a disaster. It's really criminal how quickly the body can head in the direction of couch potato when it notices you've stopped exercising.

So, for the big important race of the year:

Three weeks to go: NO MORE LONG WORKOUTS. Stress drops to maybe two thirds of normal.

Two weeks to go: Sessions drop to a third of normal. No more two-a-day workouts.

One week to go: Still working out, but short race-pace efforts to remind your body what that feels like. Rev up the engine a little and enjoy the hum, but keep it fun and keep it short.

You want to keep reminding your body that maintaining conditioning is important. But you want the overall stress and milage to go way down. As I write this I've got a sprint triathlon planned for the weekend. For this one the taper will only last a week. Three days before I'll be doing a half hour in all three disciplines. The two days before it I'm taking off. Two whole days of rest and sloth. Another approach that I've used for bigger efforts is one day on and one day off for the final week. And the days on are only something like 20 minutes for each of the three disciplines: five minutes warmup, ten minutes race pace, five minutes easy. I'm doing just enough to say to my body, Hey, I'm still using this stuff. Don't start dismantling the protein. Some coaches will you take a day off two days before an event, but then get you out exercising the day before the race. But they'll keep the workouts extremely short. Just enough to spark the engine.