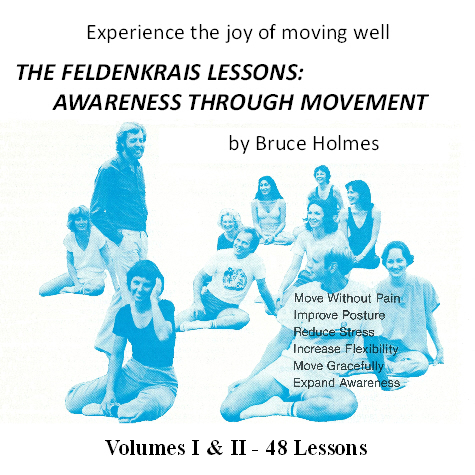

The Feldenkrais Lessons:

Awareness Through Movement

A 48 lesson home study course for $48

Moshe's Healing Touch

From Runner's World

by Bruce Holmes

It seems these days I relate everything to the running. Much of what I experience seems to flow from or relate back to it. It was the running that created my fascination with the writings of Moshe Feldenkrais, and the running added a further concern.

The technical term for my problem is chondromalacia of the knee, which simply means softness or deterioration of the cartilage. Unfortunately, giving something a name doesn’t necessarily help one deal with the situation. Whenever I got over 50 miles a week my knees would fall apart on me. I can remember occasions when I could hardly walk.

I went to the medical community for help. You know, a podiatrist, who sent me to an orthopedist, who sent me to a physical therapist… The people in the know were of the following learned opinion: I was suffering from that dreaded condition: “floating kneecap.” At some point in the future orthotics would probably be helpful, buy my most pressing need was quadriceps exercises. And if they didn’t do the job, well, there was this simple operation which they evidently do all the time.

The quadriceps exercises resulted in some very strong quadriceps, almost wrecked my back and didn’t do a thing for my running. (See note at end.) In fact, things were getting worse. The condition started cropping up at ever-lower mileages. On a couple of occasions I noticed a soft, furtive voice whispering sweetly in my ear, “Look, you’ve got hospitalization insurance. An operation wouldn’t cost a thing. You’d only be on your back a few days. They do it all the time. Your worries would be over.” But the operation never happened, and therein lies a tale.

“The Way of Moshe” rhymes, though perhaps that sounds uncomfortably spiritual. The work is more commonly referred to as the Feldenkrais exercises. But when you’ve been around the old man for a while, you’re liable to get mystical about the whole thing and start waxing poetic. The “old man” is a short, rotund, twinkling, 72-year-old Israeli by the name of Moshe Feldenkrais, probably the wisest, funniest, most fascinating man I’ve ever known.

He is the author of a unique therapy based on the vast capacity for learning which makes our species so uncommon but which also allows us to learn incorrectly. We can become creatures of habit, misusing ourselves, reacting to fresh demands with wired-in responses that are often inefficient and sometimes harmful.

The Feldenkrais work has had an enormous effect on the way I run and on the way I live my life. For anyone trying to use his or her body intelligently it is a system of thought worth considering.

The easiest place to begin might be with Moshe’s background. His doctorate was in physics, and he was a black-belt judo master, father of the judo clubs of France and author of a number of books on the subject. Even with these initial works you can see the cross-pollination, the laws of physics being applied to the operations of the body.

Then there was a knee injury that was to prove fateful. The doctors gloomily suggested surgery and refused to be optimistic about the results. Moshe didn’t like the odds and set out to find a solution on his own. He immersed himself in neurophysiology, anatomy, learning theory, biochemistry, psychology, anthropology, whatever seemed even vaguely applicable. The resultant gestalt even reflects Moshe’s study of Zen with Dr. Suzuki. And he came up with a solution of sorts. He taught himself how to use the knee correctly and, lo and behold, the body was able to heal itself.

The understandings and conclusions he had reached were presented in a book, The Body and Mature Behavior. Now, more than 25 years later, it is referred to as a pioneering work, but at the time it was largely ignored. So Feldenkrais put such concerns behind him and went back to being a physicist. Except it didn’t end there. Friends came to him with ailments, the word spread.

Finally, Moshe gave up his life’s work and at the age of 50 became a “quack.” Can you imagine the poor man’s Jewish mother whose wonderful son the physicist suddenly gave it all up for some mysterious process clearly not sanctioned by the medical world? And while Feldenkrais now uses the word “quack” with great delight, one senses that it wasn’t always so. He is a proud man and there were difficult uphill years before his work began to be recognized by the academic and medical communities.

Yet it all seems so obvious in retrospect. Our musculature does not function except as directed by the nervous system. When learning a sport we don’t train our bodies so much as our minds. The arm doesn’t learn how to hit a tennis ball properly. Instead the brain learns a complex series of neural firings in a specific pattern and time frame.

The way we hold ourselves or move is a wide array of neural impulses that is part of the brain’s normal functioning (a state which includes a complex interweave of emotions, thought, sensory impressions, spatial and temporal orientation). Change the way you move and what you’ve really changed is the nature of the mind.

In the midst of all the difficulties I was having with my knees, the Humanistic Psychology Institute was arranging for Dr. Feldenkrais to come to America to do a three-year training program in functional integration therapy. To date he had only trained a handful of associates and it was time to leave a legacy. As I applied for admission I couldn’t help remembering the story of Feldenkrais and the infamous knee injury. Maybe I’d find an answer to my own problems.

The summer of 1975 turned out to be one of the most satisfying of my life. Sixty-five of us gathered in San Francisco for the first three months of the training. We spent the mornings rolling around on the floor doing the Feldenkrais exercises: easy, gentle explorations in awareness; learning the ways in which we limit ourselves and going beyond.

“People use a mere 10% of their capacity,” Moshe was fond of saying. I suppose at times we must have looked like a gaggle of apprentice acrobats, delighting in moments of improved flexibility until Moshe brought us back to earth. “It doesn’t matter, “ he would cry. “It is a little present, but it is not the point. Was Newton flexible? No one knows and no one cares. Flexibility is irrelevant. What we are after is flexible minds.”

Before, during and after the exercises Moshe would lecture and crack jokes, insisting that unless we enjoyed ourselves we wouldn’t learn well. In the afternoons there was the table work. We had to become sensitized to the point where by touching another body we could feel what had gone wrong and with our hands help someone experience a more optimal way of functioning.

“It’s like dancing,” Moshe once explained, beaming as he waltzed an imaginary partner about. “If you take a friendly girl who can dance, and she likes you and wants you to dance, she takes you by her hand and suddenly you can dance exactly like anybody else. The two become one body, moving together. We have to establish that two-way human contact which is of the most delicate nature, so that the person feels you will guide him where he can’t go himself.”

I’d had that experience myself. When learning a folk dance with a partner who was truly confident in her movements, suddenly I’d be dancing beautifully without really being able to explain what I was doing.

Moshe’s understanding of the nervous system has applications ranging from scoliosis (curvature of the spine), to the rehabilitation of stroke victims, to multiple sclerosis (no, it can’t cure ms, but it can help people struggling with the disease to move easier), to (the wait was not in vain) helping athletes perform better. Which brings us finally to chondromalacia of the knees and my own experience of Feldenkrais.

A few days into the training I sat down beside Dr. Feldenkrais, introduced myself, asked him to forgive the intrusion, and launched into a detailed narrative of the floating kneecap and my odyssey through the medical community. As I talked his countenance grew ever more contemptuous and impatient until he finally cut me off.

“Nonsense, nonsense. Your knees hurt because you don’t know how to run. Your feet are wrong. You move your knees incorrectly. Your adductors are tight. Your pelvis doesn’t rotate. Your back is stiff. In fact, you have no movement at all between your first and second lumbar vertebrae.”

I was quickly going into shock. My faults seemed endless. And how the hell could he know all that. He made it seem a miracle I wasn’t in a wheelchair. He ended his cataloging with a mournful, “Weak quadriceps,” as he glanced to the heavens. Sometimes it seemed as if the stupidity of the world was too much for the poor man to bear.

So I was changed. My back was slowly loosened, and I started working on rotating my hips. One day it was explained to me that I was doing a hook to the outside with my left knee every time I brought it forward. On my run that night I focused every ounce of my attention on that knee, observing as uncritically as possible its position each time I pulled it through.

“There’s the arc.”

“Better.”

“Too much inside.”

“Ah, that’s it.”

By the end of the run I could tell to the centimeter whether the knee was coming through straight or not. And I had discovered a powerful tool. Awareness.

By sensing, examining, experiencing my stride, I could rid it of the extraneous. One of the central precepts of the Feldenkrais exercises is that if you pay attention to a movement, the tonus and quality will improve. “Attention, attention, attention,” the Zen master wrote when asked for wisdom. Both meditation and the Feldenkrais work can be defined as the removal of the habitual from one’s life.

On another occasion one of the Feldenkrais assistants became fascinated with my feet and commented, “Look, you have these incredibly high arches and your leg bones are directed down through the outside edges of your feet, which is where you bear the weight. You know you hold yourself like that.”

“Me? Surely the way my feet are built isn’t my fault.”

“Sure, who else? You hold your feet in an arch. Without the tightness it would be much lower. For some reason you’ve learned to hold your feet like that. Here, lie down.”

And so the mysteries began. I understand now what was done, but at the time it seemed utterly strange. For the next 30 minutes my feet were pulled, prodded, cajoled and generally shown the folly of their ways. More accurately, my nervous system was re-educated.

When I stood up it was quite unnerving. They weren’t my feet. The arches were normal, the leg bones rested squarely over the middle of the feet. Walking felt strange and even a little unsteady, quite as if I was doing it wrong.

Later that week while I was out running I re-experienced the original attitude that went with the high arch. Suddenly I was young again, imagining myself running like an Indian: strong, indomitable, tireless. I had gotten it in my head that Indians ran pigeon-toed, so there I was, cupping my feet to the inside, pulling my arches up.

The results of all this were impressive. My knee problem vanished. I’ve increased my mileage considerably without a trace of difficulty. I’m running faster than I ever did before. Last and probably least, my shoe size went from a 9-1/2 to a 10-1/2 as the feet flattened out.

I’ve come to the conclusion that correct style is important. I watch the mistakes my friends make and I’m tempted to say something. (So far I’ve kept my mouth shut, preferring slow friends to fast enemies.)

A high back-kick simply wastes time and energy.

Leaping a foot off the ground with each stride leaves you out of contact for longer periods of time and needless work is being done to attain that useless elevation.

How can your quadriceps contract freely to lift your knees if the hamstrings opposite them are doing overtime holding you up, trying to keep your forward lean from turning into a dive?

Lead with the hips and let your torso rest upright over the legs.

Try rotating your hips. Don’t worry about what the neighbors will think. A little swish can help send the knees forward and might even add an easy inch to each step. On the other hand, this can be overdone. If your elbows are flaring wide to the side, your pelvis will have to over-rotate. You don’t want this, either.

And don’t force yourself to a longer stride. If your foot lands with your leg fully extended, you’ll be braking against your forward momentum with each footfall. A shorter stride can be more efficient. Land with the knee above the foot.

I guess the best suggestion is just to become aware of what you’re doing.

The summer of ’75 was an amazing experience for me. The running seemed effortless. I was surrounded by 65 of the nicest people I’d ever met. And always there was Moshe, making us laugh, putting us through the exercises, scowling at our ineptness, telling us stories, performing minor miracles with his hands. In the end I came to love the old man, his goodness and his faults. I came away with a philosophy of life and a glimmering of what it’s all about. And an awful lot of studying to do.

A current note on strong quads

They've done research lately that shows you really can ease or eliminate knee pain by strenthening ALL the muscles of the upper leg and hips—front, sides, back, butt. The one exercise I still think has the potential to aggravate the problem is the leg extensions I was prescribed back when. But I've run across a better version of the quad exercise worth passing on. Don't do a full range of motion. Straighten the leg against resistance, hold it there a few seconds, drop the leg 6 inches and again hold for a few seconds, then extend again. This way you avoid multiple reps in the range where you aggravate the tenderness.